By Hua Ti (华提)

Issue 629, July 22, 2013

Nation, Page 16

Translated by Laura Lin

Original article: [Chinese]

Late last year, reporter Luo Changping (罗昌平) publicly accused a senior government official of corruption. Until recently, Liu Tienan (刘铁男) was the vice chairman of the National Development and Reform Commission and head of the National Energy Administration. Confident that the magazine where he works, Caijing (财经), would lack the courage to name the men, Changping turned to his personal Weibo account to make the accusations. Liu Tienan has now been expelled from the party and his case has been forwarded to prosecutors.

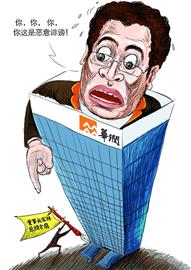

In another recent case, Economic Information Daily (经济参考报) reporter Wang Wenzhi (王文志) made serious allegations against several high-ranking executives — including Song Lin (宋林), the chairman of China Resources (Holdings) Company Limited (华润集团), a major state-owned enterprise (SOE) listed on the Fortune 500. But like Changping before him, his reporting appeared on his personal microblog account, not in his employer's print product. Again, investigators took notice.

According to Wenzhi, Lin and some of his colleagues were responsible for the loss of several billion yuan in national assets through dirty dealings during the acquisition of a stake in the Shanxi Jinye Coking Coal Group Co. Limited (山西金业煤焦化集团有限公司). Not only is Lin accused of dereliction of duty, but he also reportedly received a huge amount of money.

China Resources is a central SOE in which Lin has a high-ranking vice ministerial position. Since taking office, China's new leaders have unequivocally broadcast their intention to "crack down on the tigers as well as the flies" — meaning both major and minor offenders — saying they are determined to fight graft. The storm followed the thunder right away. In the last six months alone, 10 officials of similar high rank have fallen from grace. Such efforts demonstrate the Chinese government's commitment to punish corruption.

Relevant investigative departments will determine whether Wenzhi's reporting about the China Resources managers is accurate. According to the People's Daily, China's Central Discipline Inspection Commission, the Communist Party's anti-graft watchdog, responded very quickly to open a case. China's central anti-corruption mechanism reacted even faster and more aggressively than in the Liu Tienan case. In other words, the government seems to be working with — or at least listening to — those in civil society who are opposed to corruption (社会层面的反腐力量).

And curbing corruption within any institution or society does require cooperation. The government can't simply fight it alone. If it could, reporting mechanisms such as call-in hotlines wouldn't exist. In many countries, a civilian who blows the whistle on corruption can even be given a huge reward.

A country belongs to each of its citizens, and when their "home" is not clean, they have the right and obligation to tidy it. A reporter is first a citizen, so to denounce wrongdoing using his real name is an inalienable right.

Clearly, the recent exposés from these journalists target senior officials and executives at SOEs. Officials are civil servants whereas SOEs are the people's property. It's the journalists' duty to boldly expose any corruption they uncover.

In recent years, scandals involving SOEs have continued to surface. For instance, the case of a expensive chandelier being installed at Sinopec new headquarters, on of China's three major oil and gas companies, utterly disgusted the public. Over and over again, similar events have highlighted the serious problem of insider control.

Insider control of SOEs leads to the loss of property rights and exacerbates the unfair allocation of social resources. How to effectively improve SOE managerial structure is a weighty and important topic. So when reporters grasp facts and materials and make public allegations about official corruption, it serves as a very valuable external monitoring force.

Journalists have professional investigation skills as well as advantages in collecting information. It is inherently the media's duty to be the watchdog of public interests and is only right that they speak out against wrongdoing by governmental officials. But the fact that these exposés by journalists can become such hot news items is an indication that the Chinese press traditionally has not been effective.

What happens if an accusation by a journalist operating on his own proves to be false after a fair and truthful investigation? Can the reporter, as a whistleblower, be charged with defamation?

I am personally convinced that a non-anonymous whistleblower should be forgiven based on the idea that watchdogs of public resources should have immunity. Because only if they are protected can the public's enthusiasm for keeping an eye on those in the position of dominating public resources be maintained. It is fundamentally conducive to safeguarding public interests.

In the case of officials being wrongly accused, they can clean their name easily in today's highly developed social media environment and can avoid a damaged reputation.

On the contrary, if whistleblowers were punished, there would be a dangerous chilling effect. Nobody would dare to speak out about suspected corruption, and this certainly wouldn't be good news for protecting the public interest.

Links and Sources

Economic Observer: Xinhua Journalist Accuses Chairman of China Resources of Corruption

Economic Observer: National Energy Administration Denies Allegations Against Director

News in English via World Crunch (link)