By Shen Nianzu (沈念祖) and Chen Zhe (陈哲)

Issue 632, Aug 12, 2013

Nation, page 10

Translated by Zhu Na

Original article: [Chinese]

In 2008, a dam controlled by an unlicensed iron ore operation in the city of Linfen (临汾), Shanxi collapsed and unleashed a massive landslide on a crowded market below, killing 277. In the aftermath, Linfen Party Secretary Xia Zhengui (夏振贵) and several other officials were fired for dereliction of duty.

But Xia seems to have experienced a political resurrection, as it was recently confirmed that he’s become vice president of the Shanxi Provincial United Front Work Department. The news has once again raised questions about China’s cadre accountability system.

According to data from the Ministry of Supervision and Legislative Affairs Office of the State Council, there were over 80,000 instances of officials being disciplined in 2008. But in recent years, officials punished for events like the Linfen landslide, the Weng’an riot and the Sanlu milk scandal have one-by-one found their way back into political power.

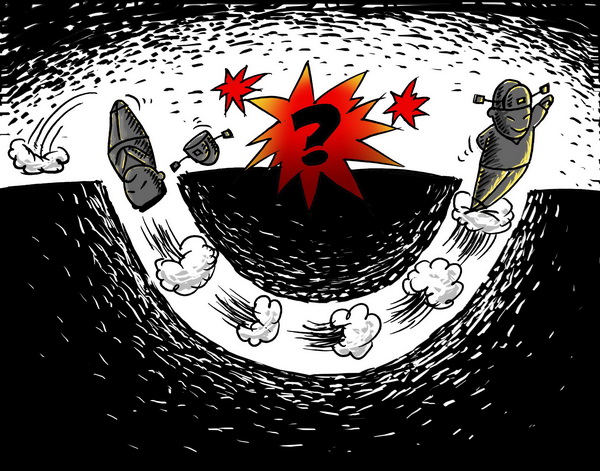

When looking back at what’s happened to officials “held accountable” for incidents over the past ten years, there’s a common pattern. First the official is fired from their position, there’s a cooling down period, and then the official quietly gets reinstated into a new position. The public then criticizes the move, whereupon the government says that the reinstatement is in compliance with regulations. The uproar then fades away, though the public usually isn’t satisfied.

Resurrected officials were most often in charge during sudden “mass incidents,” misuses of public funds for things like extravagant banquets or accidents involving food, industry or transportation.

After the 2008 Sanlu milk powder scandal, 25 officials were held accountable. Similarly, after an April 2008 train collision in Zibo, Shandong killed 72 people, 37 officials were held accountable; of which 6 were held criminally liable.

“Now when officials make mistakes there’s kind of a bad tendency to just hold them accountable,” said Zhu Lijia (竹立家), a professor at the Chinese Academy of Governance. “Even those who should take criminal responsibility eventually are just deemed ‘accountable’ without any real punishment.”

Under the government accountability system there are differences between dismissal, removal and expulsion from one’s position. Removal can precede an innocent move to a new position or it can be used after an official has made a mistake, but it has no long-term effects on their political career. Dismissal, however, is much more damaging and usually means a fall down or completely off the political ladder. Expulsion is the most serious, meaning the official is no longer eligible for public positions, and thus, has no political future.

In 2007, there was an incident in Shaanxi where a farmer collected a 20,000 yuan reward for photographing an endangered South China tiger. Local officials proceeded to tout the photo in order to promote tourism, but it turned out to be a fake. After it was discovered, the Shaanxi provincial government punished 13 cadres for the scandal.

The Economic Observer found that the civil servants with the lowest ranks, like Li Qian (李骞), an official with the Zhenping County wildlife preservation station, were expelled. Higher ranking cadres like media official Guan Ke (关克) were dismissed, but the highest ranking officials - two deputy heads of the provincial forestry department - were simply removed.

“Whenever there’s a problem exposed, the public needs an explanation,” said Wang Guixiu (王贵秀), a professor from the Central Party School. “But you have to consider that training a cadre isn’t easy, so ‘removal’ is often used. It gives the public the illusion that officials have been held accountable, but it won’t have a real impact on their political careers.”

Political comebacks have now become the norm, with few cases ending in officials being completely jettisoned. However, there’s no clear standard for when and how officials “come back.”

Looking at past cases, it appears that when officials are politically resurrected after embarrassing incidents, they’re usually first appointed to deputy positions. For example, Xia Zhengui (夏振贵), the former party sectary of Linfen, is now vice president of the Shanxi Provincial United Front Work Department. Similarly, Liu Zhijie (刘志杰), who was mayor of Linfen during the landslide, now serves as vice president of the Shanxi Provincial Agricultural Department.

The departments that resurrected officials are assigned to tend to be less attractive than their former posts. When Zhang Wenkang (张文康) was removed from his position as health minister after the SARS cover-up, he was later appointed as vice chairman of the Soong Ching Ling Foundation – an organization that promotes the welfare of underprivileged women and children.

If resurrected officials are relatively young, the new position they’re assigned to is usually more significant so that they can rebuild their political career. But if they’re nearing retirement age, they won’t usually be given very important roles.

For instance, former Deputy Mayor of Shijiazhuang Zhao Xinchao (赵新朝), who was removed because of the Sanlu milk scandal, was born in 1957 and later appointed deputy leader of the Hutuo (滹沱) New Zone leading group in Shijiazhuang and head of the city’s construction bureau. However, former Deputy Mayor of Shijiazhuang Zhang Fawang (张发旺), who was also removed because of the Sanlu milk scandal, was four years older than Zhao and got re-assigned to a much less influential position as vice chairman of the Shijiazhuang People's Political Consultative Conference.

Li Hanyu (李汉宇), vice president of the Guizhou Higher People's Court, led research on China’s official accountability system in 2008. He said that the system is essentially just decoration and can easily be used as a weapon in power struggles.