March 2011 Issue of EO's Book Review

I Denounce, I Vent, I Reminisce

[Dialogue]

Page 18-26

By Lao Yu (老愚)

Original Text: [Chinese]

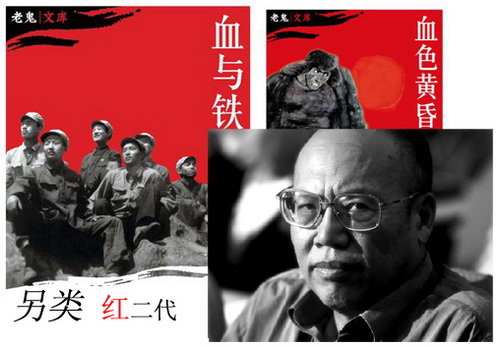

Blood and Iron (血与铁)

Lao Gui (老鬼)

New Star Press, Oct 2010

As the son of communist revolutionaries, Lao Gui(老鬼) wanted to carry on the revolutionary struggle. A trying childhood led him to his literary calling.

Lao Gui wrote a trilogy of Chinese contemporary history from 1951-1989, Blood and Iron (血与铁), Blood Twilight (血色黄昏), and Blood Dawn (血色黎明).

His works are memorable for their black-and-white morality, and are populated by clear-cut heroes and villains and marked by devastating moral decisions.

Lao Gui captures the experiences of the Hong er dai (红二代) the second generation of red revolutionaries. He and his contemporaries are simultaneously passionate believers and cold skeptics, seized by questions of right and wrong, loyalty and betrayal.

The following are excerpts from the interview with Lao Gui:

Lao Yu: When did you begin recording Chinese modern history?

Lao Gui: I didn't think I was recording history. I was just describing what I observed happening around me. When I was in the construction corps in Inner Mongolia, I was arrested as an anti-revolutionary. I experienced a lot of terrible things. I thought to myself, I have to write about this, I have to let people know.

Lao Yu: You hoped that your writing was not only a source of personal comfort but a warning to wrongdoers. Do you think it has been effective as a warning?

Lao Gui: In Blood Twilight I tried to render, as realistically as possible, what happened to us. No one's ever taken issue with me for what I wrote. No one came and said I ruined their reputation or that I was unreasonable.

(….)

Lao Yu: Having left your homeland, the events of your childhood must have seemed much more vivid. I'd like to ask you to describe your emotional and mental state when you wrote Blood and Iron.

Lao Gui: Geographically, America and China are similar. But the US has one sixth the population of China. There are very few people around during the day. When I arrived in America, the most terrible thing about it was the isolation, the loneliness.

Lao Yu: There was no one to talk to?

Lao Gui: Yes, that is the worst, most terrifying thing about it. China is lively and bustling with people; it's not like that in the US. At Christmas, every house has lights and a Santa Claus out front. It's beautiful, but it's quiet, almost like a cemetery. There’s no one in the streets. I lived in a mid-sized city; small cities are even quieter. I was lonely in the US and I thought about my friends, my family, my classmates ... this is what I was doing when I wrote Blood and Iron.

Lao Yu: In Blood and Iron you described a type of education based on "revolutionary heroism," has this education left a lasting impression on you?

Lao Gui: ... I care about national affairs because of my education. Before I wanted to shed blood and sweat for the revolution. But there's no revolution now. The meaning of the word "revolution" has changed.

Lao Yu: Into what?

Lao Gui: National and social progress. I care about these.

Lao Yu: Are you going to write about the period from '89 to now?

Lao Gui: I don't think I can ... I don't have the energy.

What Does Harry Potter Have in Common with the Heroes from Jin Yong's Martial Arts Novels?

[Focus]

Page 3-5

By Wang Miao (王淼 )

Original Text: [Chinese]

Reviewer Wang Miao walks us through the similarities and differences of the education of Harry Potter and the journeys of self-realization that take play out in Jin Yong's martial arts novels.

At Hogwarts and in Jin Yong's novels, distinctions of character begin not with inherited fame or wealth but with the heroes' unique talents and how they use them. Jin Yong's hero Zhangquji and Harry are both orphans, and these children of renowned martial arts masters and famous wizards are forced to prove their individual worth based on merit, and not pedigree.

In Jin Yong's world, education is a process of self-discovery. Heroes learn about themselves and discover their capabilities by trying them out.

J.K. Rowling's Hogwarts offers an indictment of bureaucratic learning methods. According to Rowling, only so much can be taught. Capable, educated individuals mature through applying what they learn in a practical setting.

In both, teachers and mentors are portrayed as flawed human beings and as indispensable role models and a source of personal guidance.

Most of all, the Harry Potter books and Jin Yong's novels offer insight into becoming an adult and learning to shoulder one's responsibilities in the world.

Portrait of Journalist Yang Jisheng (杨继绳)

[Books and Portraits]

Page 6-11

By Xu Qingquan (徐庆全)

Original Text: [Chinese]

30 Years Hedong (三十年河东)

Yang Jisheng (杨继绳)

Wuhan Publishing House, Mar 2010

Xu Qingquan, the deputy editor in chief of Yanhuang Chunqiu magazine, discusses Yang Jisheng:

I have been a colleague of Yan Jisheng for ten years. I still find him a poor conversationalist. When he talks, there is always a barrier.

First, he has a heavy accent. Yang Jisheng comes from Xishui in Hebei Province. He has lived in the Beijing and Tianjin area for over 50 years, but he has kept his provincial accent. He is lively and animated when he talks. But when he’s done talking, no one has any idea what he was on about.

Second, he looks at everything from the "historical" perspective ... He deals with conclusions and not with how he got there ...

Third, he has no sense of humor. No matter how familiar you get with him, you can't joke around with him ... You can be laughing away, but he won't even crack a smile.

He graduated from Tsinghua University, and worked at the Xinhua News Agency for many years. But he still dresses like a farmer, or a low-ranking official from the 70s and 80s.

... I got to know him over the years, and I came to understand why he is like this. He comes from a poor family in rural Hebei, and lost his father to the famines of the "Three Bitter Years." His career as a journalist was built around his hardships.

Yang Jisheng worked for the Xinhua News Agency for over thirty years. He joined in 1968 and retired in 2000. As a student, Yang's dream had been to become a journalist ... . He initially attended Tsinghua University for mechanical engineering.

Yang has few fond memories of his alma mater ... he was sent to the countryside almost immediately to defend the "Three Red Banners".

As Yang recalls, there were few books in the library, except Marxist writings. The library gave him the impression that capitalism, and other political and economic thought before Marx can be summed up in the phrase "cause for rebellion," and that "socialism" can be summed up with one word: "good."

Yang's career in news can be divided into three stages. The first stage lasted from 1968 to 1977 at the Tianjin branch of Xinhua ... . Looking back, the 70 year-old Yang said, "I'm ashamed when I think about this period of history. Journalists were not told to be objective, but to stick to the party line. The party's eyes are your eyes, and if you attempt to be objective, you were 'on the wrong side.' Those ten years were about following trends and writing in the language of revolution, the language of the party. ... When I looked through what I wrote in later years, I felt like 90% of the articles should have been burned."

…

Of the next ten years, Yang recalls "This is the period of the reform and opening up. This began a golden age of Chinese journalism; the profession came alive. During this time, drafts were changed and edited but there was room for original reporting and an independent viewpoint. You weren't always telling the truth, but you couldn't tell lies anymore."

In February 1993, Yang wrote his famous "Political Power Should Not Enter the Market" (权力不能进入市场), an article which cautioned against the abuse of government power during China's rapid economic development.

According to Yang, China today marries capitalism with "authoritarian politics. In this system, greed is married to capital which becomes the source of social problems." The Price of Subcultures: Ryu Murakami

The Price of Subcultures: Ryu Murakami

[Literature]

Page 15-17

By Hosseini

Original Text: [Chinese]

Almost Transparent Blue (无限近似于透明的蓝)

By Ryu Murakami (村上龙)

Translated by Zhang Weicheng (张唯诚)

Shanghai Translation Publishing House, Jan 2006 (Original published in 1976)

Ryu Murakami will turn 66 next year. The author who penned some of Japan's most beloved and most disturbing novels in his youth, is now a filmmaker, an economics commentator and a gourmand.

Murakami began his career as a literary rebel with Almost Transparent Blue. The book's depiction of Japans' youth shocked his reviewers and created an instant sensation. His was a type of novel that did not appropriate western tropes for an eastern audience.

His novels, which include Coin Locker Babies and Audition (now a popular film), are sharp but dark, full of humor, but unabashedly pessimistic.

Murakami attracted a Chinese audience because his dark themes responded to some of the lamentable aspects of modern society in the east, abandonment and loneliness.

His autobiography 69 mostly addresses his experience of traveling around the world. Older and wiser, Murakami never lost the adolescent in him, or the themes of loneliness and despair. He is an author with a keen and penetrating eye that remains a towering figure in Japan's literary word.

Daniel Bell: Remembering the Master

[Academic]

Page 34-36

By Zuo Ye (左页)

Original Text: [Chinese]

The Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism (资本主义文化矛盾)

The Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism (资本主义文化矛盾)

By Daniel Bell

Translated by Yan Beiwen (严蓓雯)

Jiangsu People's Publishing House, Sep 2007 (Original published in 1976)

Any discussion of the culture of capitalism is incomplete without a mention of Daniel Bell. Bell's presence can be felt and detected in the works of his contemporaries and successors, even when he is not explicitly cited.

Daniel Bell, sociologist, economist, author, editor, and Professor Emeritus at Harvard University, passed away on January 25th, 2011. He has been credited with the concept of the "post-industrial" society, and with his insights into the alienating aspects of modernity, and the negative social impact of capitalism in the developed world.

Bell's work is hard to categorize, as it has had an impact on the fields of literary studies, literary theory, criticism, economics, politics, sociology and others.

He published the The Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism in 1976, on the heels of The Coming of a Post Industrial Society, published in 1973, and The End of Ideology, published in 1960. In his books, Bell engages with the writings of Marx, Weber, Berlin, and more.

For Bell, the culture of capitalism is self-destructive because it destroys what it celebrates, namely, individual innovation and work ethic. When we read it now in 2011, it's obvious that Bell's work did not adequately address the economic and cultural realities of the decades that followed the publication of his book. But it was provocative and remains hugely influential as theorists continue to reassess the conditions of global capitalism.

You can download a copy of the March 2011 issue of the EO's Book Review here.

Links and Sources

EO's Book Review: Official Site

Douban: EO's Book Review

Economic Observer: February Issue of EO's Book Review

Economic Observer: January Issue of EO's Book Review

The views posted here belong to the commentor, and are not representative of the Economic Observer |

Related Stories

Popular

- BOOK REVIEW

- March 2011 Issue of EO's Book Review

- Highlights from this month's issue of EO's Book Review

Interactive

Multimedia

- EEO.COM.CN The Economic Observer Online

- Bldg 7A, Xinghua Dongli, Dongcheng District

- Beijing 100013

- Phone: +86 (10) 6420 9024

- Copyright The Economic Observer Online 2001-2011